An Exercise in Freedom

Researching Bodily Performance in Electronic Music

“Non-knowing is not a form of ignorance but a difficult transcendence of knowledge. This is the price that must be paid for a work to be, at all times, a sort of pure beginning, which makes its creation an exercise in freedom.”

(Lescure 1956) cited in (Bachelard 1957, p. 24) [1]

This quote from the middle of the last century delineates in a beautiful way the crux of artistic creation but also of research in the domain and with the methods of the arts. If one of the definitions of research is the creation and dissemination of new knowledge, then the obligation for art as research to fulfil this criterion is evident.

Before getting to the topic of the body in performance, let’s examine the question of the role and the types of knowledge artistic practice and research has in comparison to scientific or scholarly research. Scientific research is defined to be “original investigation undertaken in order to gain knowledge and understanding” or ”a careful study or investigation based on a systematic understanding and critical awareness of knowledge”. (Borgdorff 2007, p. 9) As Elkins points out, in the arts, knowledge and understanding is not a result or outcome commonly expected, neither by the artists nor by their public. [2] (Elkins 2009, p. 116)

Any artistic process contains these core elements, along with other aspects specific to the domain of artistic expression. The main difference is in the type of knowledge produced. Whereas scientific research incorporates and extends all the knowledge of a specific field, the artistic knowledge is unique and bound to the art object: it resides in the experience it elicits, or whatever form of perception the artistic process has generated. (Slager 2009) Therefore the aesthetic moment can only be located in the ‘non-knowing’ or pure beginning. In both worlds, true research doesn’t primarily look for answers, but for the right questions to ask. (Nersessian 2008) (Koestler 1964)

The state of ‘non-knowing’ and this ‘difficult transcendence’, however, is common to any arts practice, since its core elements are present merely in ‘tacit’ and sometimes ‘embodied’ ways. The kind of tacit knowledge embedded in an art-object [3] (Jones 2009) is the result of the deliberate act and conscious creation process on the part of the artist and represents on the one hand the worldview and pre-experience of the individual artist, and depends on the other hand on the social context within which the art-object is perceived. [4] (Slager 2009, p. 52)

This experience-based knowledge is not dissociable from its artistic process and object and may be situated as much within the artist as within the perceiving public. It occurs only in the presence of the art-object itself, and will take on different forms and represents a first kind of “knowledge in action”. (Schön 1995) This presupposes an intrinsic intelligence (Jones 2009, p. 32) that is contained within the art process and is made available or released in its primary form within the experience of the art object itself. [5] (O’Riley 2005) Borgdorff calls this the ontological domain, where through the materiality of the medium an aspect presents itself which transcends materiality. (Borgdorff 2007, p. 12)

The second kind of knowledge, which is more closely related to a scientific practice, can be called “knowledge on (by) reflection”. This new knowledge [6] is articulated in a different way and has to be poured into a form, which is distinct from the art-object itself. A condition for this is that in a reflective moment, the primary, non-verbal knowledge embedded within the art-object is perceived, understood and transformed into thought and a textual or verbal manifestation of knowledge. [7] (Elkins 2009, p. 125)

Before we go on, a few words about my background and my motivation for pursuing this artistic investigation in an academic context.

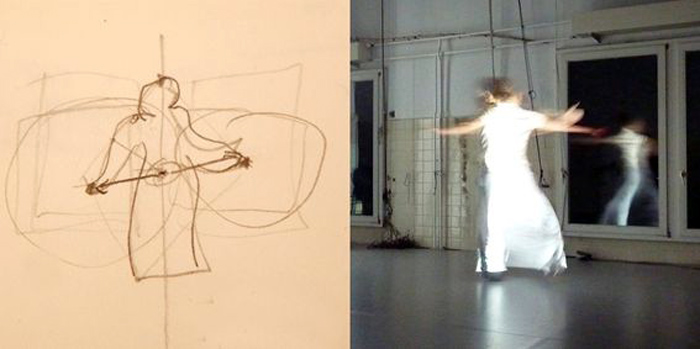

Currently I am pursuing an artistic doctorate at the Orpheus Instituut in Ghent, and the Royal Conservatory in Antwerp, Belgium. For my doctoral project I am constructing an investigation, which on a theoretical level goes into the underlying psychological and philosophical aspects inherent to performing music on stage, and on an artistic level builds a deepened relationship between my practice of musical creation and performance and extended forms of artistic work. Of course, this investigation deals with a specific style of music and context and addresses a specific way of performing, interpreting and even creating music – or other forms of art. These contain the essential element I’m striving for in art – a quality of shared experience and immediacy in presence that is unique to live performance (see Figure 1).

My background is as a double-bass player in jazz and free playing (in parallel with classical orchestral training), later as an electro-acoustic composer and electronic performer, and finally as a media artist. Over the years my works and aesthetics have evolved across those fields, engendering a style of creation and performance that contains elements of all my previous incarnations as a musician and my other artistic interests. [8] The core elements that have been constant in my work are the exploratory attitude through performance and improvisation, working on stage, or in the case of installations, in clearly defined gallery spaces, and the necessity to search for abstraction from common artistic idioms.

This is why the central research question for my project is derived from the experience as a music performer on stage. In particular, I’m interested in the state of body and mind in exploratory, improvised music situations. I’m inquiring into what the inner and outer aspects are, which constitute a fully present, aware and embodied music performance in a technologically mediated music practice. A number of heterogeneous elements come into play in this constellation, which are situated both within the outward context and circumstance of performing this way and the inner processes of awareness and perception occurring with the musician.

Since my practice involves the use of technical tools and instruments, I’m especially interested in the contradiction between the corporeal space of performance and the abstract, codified world of digital processes. Instruments that exist in the symbolic domain (i.e. in software) and are accessed through non-specific interfaces or objects, pose the question of what the role of non-reflective body-awareness may be. With these instruments, the physical actions that have been imprinted into a body-schema don’t conform to the characteristics of traditional physical and sound-generating instruments. This (pre-)cognitive dissonance between affordances and action spaces, object representations and actual instrument complexity can lead to a break-down of bodily self-awareness. The intentionality that is necessary to play a traditional instrument remains, but the sense of agency that the non-reflective body perception of physical sound production renders possible, disappears. (see Figure 2)

In my pieces, the stage situation is sometimes modified to question the conventional frontal presentation mode. In other instances, the traditional situation is maintained in order to focus on more intrinsic aspects of performing the piece. This outward aspect deals with the social dimension of a musician’s work and has repercussions not only on the audience but alters the way a musician feels, behaves and acts as well. Furthermore, in any reflection about the stage situation, the social and individual implications and the cultural context cannot be neglected, since they strongly inform both the musician’s and the audience’s state in the psychological domain. This is especially true when considering the ritual role taken on by the musician in the charged and heavily encoded situation of the stage.

The significance of the act of performing, its impact on oneself and others is put succinctly by Evan Parker when he says: “[T]he aim is not to ‘let sounds be sounds’ or however Cage put it, but to acknowledge the fact that producing the sounds means something to you, being in control of the sound means something to you, interacting with the other players means something to you. And have the outcome, the musical outcome, be at least an expression of those things.” (Lock 1991)

When taking the body as a focal point for an investigation about performance on stage, it is essential to examine the corporeal issues of the performance and, above all, the psychological aspects of bodily perception and physical presence this involves.

The fundamental attitude aimed at by any performer, be it in theatre, dance, music or even performance-art, is that of complete focus, awareness on as many levels as possible and utter presence in the ‘here and now’. (Schechner 2003) Part of that state is described by the concept of ‘flow’. (Csikszentmihalyi 1990) In a performing-arts context it is also called “stage presence”. [9] This represents a primary level of communication with the audience and transports an important part of the affective potential of the performance. The intangible elements that constitute the ‘stage-presence’ of the musician creates a phenomenon that occurs between the performer and the audience and can be identified as belonging to the categories of the performative bodies, awareness, agency and consciousness of self.

In order to better understand what this presence could be constituted of, specific elements of bodily perception need to be identified. Based on the concepts elaborated in the ‘enactive’ and cognitive philosophy of the last two decades, Legrand proposes the distinction between four types of body perception: the opaque body, which is the object of an observational body experience; the invisible body, which is absent from experience, the transparent body, which is experienced only ‘as one looks through it to the world’ and finally the performative body, which involves a non-reflective, immediate experience of the body. (Legrand 2007)

The observational awareness or attention, which is directed towards the musical elements that are being performed, is always peripherally framed by the transparent body perception, be it with regard to the situated-ness on stage or particularly in the interaction with other musicians. Musically, a perception occurs that is non-reflective and forms part of an overarching musical awareness concerned with global control.

The best example for this type of awareness is the perception of musical forms, especially of longer duration. It occurs through a low-level listening, a sort of non-reflective, reduced listening (Schaeffer 1966), with neither conscious involvement nor attentional focus. Interestingly, the non-reflective awareness of musical elements can, with habituation, sink to the even lower level of somatic proprioception. In this way, the loop is closed between the musical awareness played out on a symbolic or even metaphorical level (Lakoff and Johnson 1980) and the sensory-motor integration in the body.

An example for this is the perceptual skill of intonation, which is the capacity to fine-tune the pitch of a note on instruments, which don’t offer a static system of tuned notes, such as strings or horns. Through long periods of ‘atunement’, the musician can obtain the capacity for a sort of ‘instinctive’ pitch correction, related either to other voices within the music [10] or in relationship to the sonic characteristics of a single instrument. Another example is rhythm and the micro-timing effects that occur when complex rhythms ‘lock’ or ‘groove’, such as in African, Afro-Cuban or Jazz music. (Meelberg 2011)

On stage, awareness, both on the non-reflective and reflective levels, is the foundation of a performance that mobilises the full potential of the musician. It may seem odd to tie awareness of a musician on stage directly to the instrumental performance and corporeal presence. However, this is indeed the musician’s main field of action. It is here that the concept of ‘performativity’ can be applied directly, in an analogous manner to awareness, and it is here that ‘agency’ becomes a necessary constituting element of the performance. “This performative awareness that I have of my body is tied to my embodied capabilities for movement and action. [...] my knowledge of what I can do [...] is in my body, not in a reflective or intellectual attitude [...]” (Gallagher 2005, p. 74)

The sense of agency is important for the higher level of self-awareness that is necessary to perceive and maintain the coherent stream of perception and actions that make up the musical performance. It is also a constitutive element of the low-level processes the body establishes to guide its actions. “[...] the sense of ownership for actions depends on sensory feedback for proprioceptive, visual tactile sources. It is generated as action takes place. The sense of agency, however, is based, in part, on pre-motor processes that happen just prior to the action.” (Gallagher 2005, p. 237)

The crucial question raised by this discussion about the wider context of artistic research in general and the core elements of my doctoral project in particular, is the one about methods. It’s all well and good to add a reflective layer to a creative practice that can explain or justify certain choices. But these reflections are without significance if they do not produce consequences within the process of the practice itself. Solutions need to be found to the issue of how the practice may be methodically modified, extended or augmented, without losing the essentially intangible core of it. What are the methods that help generate the desired knowledge? Which are the appropriate forms of its dissemination? It would not do to merely adapt methods from the hard sciences, such as the experimental settings with clearly defined parameters and hypotheses, and the analysis based on empirical data.

The kinds of information that transport the insights and the understanding coming out of an artistic process need to be found in a different domain. Since human experience is at the heart of the art object, methods from social sciences may help to collect traces of these subjective moments. These are for instance memory protocols, interviews and similar ways of gathering qualitative data, which may be adapted from ethnography to provide a corpus of texts that afford an additional perspective. A comprehensive documentation in photographic, video-and audio-formats of both the extended preparation phases and the actual compressed performance moments may also serve as a basis for reflection (see Figure 3). Finally, when directed at the heart of the creation process, special attention should be given to preserving the order of elements and chains of associations (James 1896) that are at the origin of the creative impulse. [11]

Needless to say, all of these activities modify the artistic processes in the creation of pieces and their performance. The blending of the three spaces (Fauconnier and Turner 2003) in my project – the performance and creative practice, the collection of traces and their reflection, and the investigation into the psychology and philosophy of mind – has an impact on the way I create pieces, on the awareness I have on stage and on the expressive power of my work as it is experienced by others. Arguably, this is the type of ‘non-knowledge’ that might be exposed as the real result of an artistic research process.

Contrary to what one might think, this artistic investigation and academic project – instead of narrowing the scope by adding layers of analysis and reflection – allows me to expand essential skills for performance such as the bodily awareness on stage, the ability to transcend the limitations of tools and instruments, and the necessity to be in an open and communicative attitude, both on stage and off. In this sense the research project enriches my expressive space and gives more freedom to the intangible, essential elements that make up a unique artistic experience.

Notes

1 “Le non-savoir n’est pas une ignorance mais un acte diffcile de dépassement de la connaissance. C’est à ce prix qu’une oeuvre est à chaque instant cette sorte de commencement pur qui fait de sa création un exercice de liberté.”

2 “...For the majority of artists, knowledge isn’t what art produces. Expression, yes, Emotion, passion, aesthetic pleasure, meaning. But not usually knowledge...”

3 I intentionally use the term object instead of work, because there are many forms of artistic creation that defy the closed off, separate position the term work evokes. Nevertheless I think that processes, artifacts, traces, situations, impressions and experiences form an object – even if only in perception – that can be treated as an entity. And this is in my opinion “Knowledge embodied or represented by an object”.

4 “In contrast to academic-scientific research emphasizing the generation of ‘expert knowledge’, the domain of art seems rather to express a form of experience-based knowledge whereas pure scientific research often seems to be characterized by academic goals, [...] artistic research focuses on the involvement, on social and non-academic goals.”

5 “A work’s meaning is found neither in the work itself, nor in the hands, eyes or minds of the artist or viewer... it is apparent only in the space between them.”

6 This can also be also called ‘insight and understanding’. I haven’t found a good translation for the German term “Erkenntnis” into English. Perhaps the moment of recognising, realising, when knowledge becomes apparent in the individual mind is what the German term “erkennen” and “Erkenntnis” denotes. In this context I’m using ‘New Knowledge’ or ‘Epistemic Knowledge’ to signify this.

7 “[...] In this theory, it should not be possible to articulate the pertinent thoughts or arguments that are embedded in the artwork. If that were possible, then the claim would not be that the artwork embodies thought, but that it enables thought [...] Here the claim is that whatever counts as knowledge or research simply is the artwork.”

8 These includes activities such as abstract drawing/painting, building instruments, creating and collaborating in installations works, or dealing with sound in the landscape.

9 “Through the presence of the performer, the viewer experiences the performer and at the same time herself as an embodied mind, as a continuous ‘becoming’. The circulating energy is perceived as a transformation force – and in this sense as a life-force.” (Fischer-Lichte 2004, 171, author’s translation), see also (Varela, Thompson, and Rosch 1991)

10 Good examples are string quartets, where the players develop a high sensitivity to harmonic tension, which they regulate through fine-tuning of the pitches in relation to each other.

11 Of course the critical question here is ‘how’? Introspection during the creative moments can only go so far, since it interferes with the process. Retrospective gathering of hints and traces seems to be the only way, with the problem that our memory for the kinds of ‘chains of associations’ or ‘stream of consciousness’ (James 1896) is extremely limited in time. Short-term memory for example is said to only last for about 45 seconds. (Damasio 2000)

References

BACHELARD, G. (1957). The Poetics of Space. 1994, Beacon Press, Boston, MA. Bibliothèque de philosophie contemporaine. Les Presses Universitaires de France.

BORGDORFF, H. (2007). “The Debate on Research in the Arts”. In: Dutch Journal of Music Theory 12.1.

CSIKSZENMIHALYI, M. (1990). Flow: the Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper and Row.

DAMASIO, A. (2000). The Feeling of What Happens – Body, Emotion and the Making of Consciousness. London: Vintage, Random House.

ELKINS, J. (2009). “On Beyond Research and New Knowledge”. In: Artists with PhDs. Ed. by J. Elkins. New Academia Publishing, pp. 111–133

FAUCONNIER, G. and M. TURNER (2003). The Way We Think: Conceptual Blending and the Mind’s Hidden Complexities. Basic Books.

FISCHER-LICHTE, E. (2004). Aesthetik des Performativen. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag.

GALLAGHER, S. (2005). How the Body Shapes the Mind. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

JAMES, W. (1896). The Principles of Psychology. Henry Holt and Company.

JONES, T. E. (2009). “Researching Research in Art and Design”. In: Artists with PhDs. Ed. by J. Elkins. New Academia Publishing.

KOESTLER, A. (1964). The Act of Creation. London: Penguin Books.

LAKOFF, G. and M. JOHNSON (1980). Metaphors We Live By. University Of Chicago Press.

LEGRAND, D. (2007). “Pre-Reflective Self-Consciousness: On Being Bodily in the World”. In: Janus Head 9.2, pp. 493–519.

LESCURE, J. (1956). Dessins de Charles Lapicque, La mer. Paris: Flammarion.

LOCK, G. (1991). “After the New: Evan Parker, Speaking of The Essence”. In: The Wire 85, pp. 30–33, 64.

MEELBERG, V. (2011). “Moving to Become Better: The Embodied Performance of Musical Groove.” In: Journal for Artistic Research 1.

http://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/?weave=16068.

NERSESSIAN, N. J. (2008). Creating Scientific Concepts. MIT Press.

O’RILEY, T. (2006). “Representing Illusions”. In: Thinking Through Art - Reflections on art as research. Ed. by K. Mcleod and L. Holdridge. Routledge, pp. 92–105.

SCHAEFFER, P. (1966). Traité des Objets Musicaux. Paris: Editions du Seuil.

SCHECHNER, R. (2003). Performance Theory. Routledge.

SCHÖN, D. A. (1995). The Reflective Practitioner. Ashgate Publishing; New edition.

SLAGER, H (2009). “Art and method”. In: Artists with PhDs. Ed. by J. Elkins. New Academia Publishing, pp. 49–56.

VARELA, F. J., E. T. THOMPSON, and E. ROSCH (1991). The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience. Cambridge Mass: MIT Press.

About the Author

A doublebass-player, composer and digital artist, Jan Schacher is active in electronic and exploratory music and media work. He has a background in jazz, contemporary music, performance and installation art as well as writing music for chamber-ensembles, theatre and film. His main focus lies on performance works combining digital sound and images, abstract graphics and experimental video and gestural interaction in the field of electro-acoustic music and in electronic arts for the stage and in installations.

Jan Schacher has been invited as artist and lecturer to numerous cultural and academic institutions and has presented installations in galleries and performances in clubs and at festivals such as the Sonar Festival (Barcelona), Transmediale Festival (Berlin), the Holland Festival and the Sonic Acts Festival (Amsterdam) the Singapore Arts Festival, the Edinburgh International Festival, the Sonic Circuits Festival (Washington DC) and many other venues throughout Europe, North America, Australia and Asia.

In addition to his artistic work, Jan Schacher is an Associate Researcher at the Institute for Computer Music and Sound Technology of the Zurich University of the Arts. In the context of research he is investigating and developing methods for spatial sound projection, interactions in dance and live-electronic music. He has published peer-reviewed articles and contributed to publications about the performance practice in digital arts. Jan Schacher is currently pursuing an Artistic Doctorate at the Royal Conservatory Antwerp and the Orpheus Institute in Ghent, Belgium.

Publications by the Author

Jan C. SCHACHER (2013a). “The Quarterstaff, a Gestural Sensor Instrument” In: Proceedings of the Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME 2013), Daejeon & Seoul, Korea Republic.

Jan C. SCHACHER (2013b). “Hybrid Musicianship – Teaching Gestural Interaction with Traditional and Digital Instruments” In: Proceedings of the Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME 2013), Daejeon & Seoul, Korea Republic.

Jan C. SCHACHER (2012). “The Body in Electronic Music Performance” In: Proceedings of the International Sound and Music Computing Conference (SMC 2012), Copenhagen, Denmark.

Jan C. SCHACHER (2011). “Traces – Body, Motion and Sound” In: Proceedings of the International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME 2011), Oslo, Norway.

J. C. SCHACHER, D. BISIG, and M. NEUKOM (2011). “Composing With Swarm Algorithms – Creating Interactive Audio-Visual Pieces Using Flocking Behaviour” In: Proceedings of the International Computer Music Conference (ICMC 2011), Huddersfiled, UK.

Jan C. SCHACHER (2010). “Motion To Gesture To Sound: Mapping For Interactive Dance” In: Proceedings of the International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME 2010), Sydney, Australia.

Jan C. SCHACHER (2009). “Action and Perception in Interactive Sound Installations: An Ecological Approach” In: Proceedings of the International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME 2009), Pittsburgh, USA.

Jan C. SCHACHER (2008). “Davos Soundscape, a Location Based Interactive Composition” In: Proceedings of the International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME 2008), Genova, Italy, 2008.

Jan C. SCHACHER (2007). “Gesture Control of Sounds in 3D Space” In: Proceedings of the International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME07), New York, USA.

J. C. SCHACHER and M. NEUKOM (2007). “Where’s the Beat? Tools for Dynamic Tempo Calculations” In: Proceedings of the International Computer Music Conference (ICMC 2007), Copenhagen, Denmark.

Comments

Log in to comment.